The Dancing Plague

This article was first published in Literatief 38.1 by Literary Student Association Flanor in 2023.

Introduction

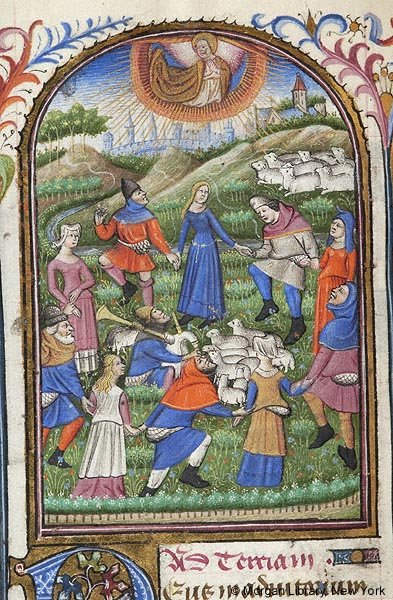

One of the earliest known records to mention the ‘dancing sickness’ is found in Germany from the year 1021. Eighteen people were said to come together in the churchyard of the town Kölbigk. Here they would dance to their heart’s desire. They danced throughout the mass, to the chagrin of the local priest. So, he cursed them. Once cursed, they could not stop even if they wanted to. They danced unceasingly, like living dead, for a full year until the curse was lifted and each person collapsed, either from exhaustion or because they had danced themselves to death.

A European phenomenon

While this story appears to be Christian doomsday writing, there are in fact dozens of chroniclers recounting dancing manias throughout history, the most famous stories being the from 1374 and 1518. These records talk of people dancing in agony for days or weeks at a time. There have been cases recorded in Germany, the north-east of France and the Low Countries. Some people were crying of visions that were so terrible they believed themselves to be possessed. Other victims, it is said, barely recalled their hysteria when they awoke from their trance-like state. Records of the disease can be found in both sermons and writings of famous figures such as Paracelsus (d.1541). In the Middle Ages several remedies were attempted to stop the sickness. A popular remedy was to play music as this was thought to cure the soul. As the epidemic was of a dancing nature, however, music has also been argued to make matters worse. Another cure was to pray to St. Vitus or St. John the Baptist who were thought to have brought about the curse in the first place. For this reason the dancing mania has also been called the St. Vitus’ dance.

From a modern perspective we can argue further than God’s wrath. So what else could have been the historical cause of the dancing mania? Some scholars have suggested ergot poisoning which is caused by the ergot fungus that infects rye and other cereals that were frequently consumed at the time. Symptoms of ergot poisoning mirror those of dancing mania as people complained of painful seizures, spasms, paresthesia, psychosis and nausea. While ergot poisoning could have been a likely cause, it has not been confirmed with certainty. Historians of science such as John Waller are more in favour of a psychological explanation for the mania such as PTSD from the Black Plague. Another popular explanation is Mass Psychogenic Illness (MPI). One of the most fascinating things about Mass Psychogenic Illness is that it still baffles scientists today. According to Robert Bartholomew, one of the leading experts on the topic, the symptoms of MPI include hallucinations, headaches, nausea, spasms and fainting.

Amidst our people here is come

The madness of the dance.

In every town there now are some

Who fall upon a trance.

It drives them ever night and day,

They scarcely stop for breath,

Till some have dropped along the way

And some are met by death.

– Straussburgh Chronicle of Kleinkawel (1625)

Curt Sachs, World History of the Dance

Research on MPI illustrates that to be affected by the mania, the group in question has to perceive the threat or the cause of their suffering as credible. So while we can raise our brows at the validity of the dancing plague epidemics, it may have been a very real threat to those who suffered from it. While ergot poisoning and dancing mania are things of the past, Mass Psychogenic Illness is not. Bartholomew’s literary review shows that the somatic symptoms as described above are found in all populations, especially under stressful conditions. While anyone can succumb to MPI, women appear to be particularly affected. This is likely because of the strenuous circumstances in which women had to live. Many cases of dancing mania as well as MPI concern women who lived under poor, oppressive circumstances. Think of nuns showing signs of demonic possession in the middle ages and girls going mad at boarding schools in the 1900s. While there have been no conclusive answers to the cause or cure of the dancing plague, it sure did provide a source of fascination for scientists, historians and authors. Most cases seem to derive from stressful or oppressive circumstances, so the psycho-physical symptoms could very well be a reaction of the human body to those circumstances. The mystery around the whole dancing plague phenomenon makes it an often studied topic for both historians, psychologists and writers.

Some suggestions of media dealing with the phenomenon

- The Sin of Sacrilege (early 1300s) — A Middle English rendition of the Kölbigk tale in which a priest curses the dancers in his parish and by doing so he brings about his own daughter’s death.

- The story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin — Some versions more bed-time friendly than others.

- Da Vinci’s Demons 1×04 ‘The Prisoner’ — At a Florentine convent nuns suffer from a mass demonic possession, but the true cause of the madness might be more material.

Sources

Bartholomew, Robert; Wessely, Simon (2002). “Protean nature of mass sociogenic illness”, The British

Journal of Psychiatry 180 (4): 300–306. doi:10.1192/bjp.180.4.300

Waller J. A Time to Dance. A Time to Die: The Extraordinary Story of the Dancing Plague of 1518.

Cambridge: Icon Books, 2008.

Sachs, C., World History of the Dance, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1937.